The year since President Jimmy Carter’s death seems an echo of the years leading up to his 1976 election, when he won the White House with a call to healing, decency and truth.

His most recent biographer, Jonathan Alter, noted this and predicted recently that in the next decade America will see a figure emerge like Carter did after Watergate to successfully call the country to its better angels.

Should Alter’s prediction come true, that leader will have Carter’s moral imagination, the ability to envision how the world can be better and how suffering can be eased.

But the president didn’t stop with the vision. He then focused on action to make progress toward that better world, to show individual responsibility for the common good. As his White House Chief of Staff Hamilton Jordan wrote, most of us want to make the world a better place; Jimmy Carter started every day with a plan to do it.

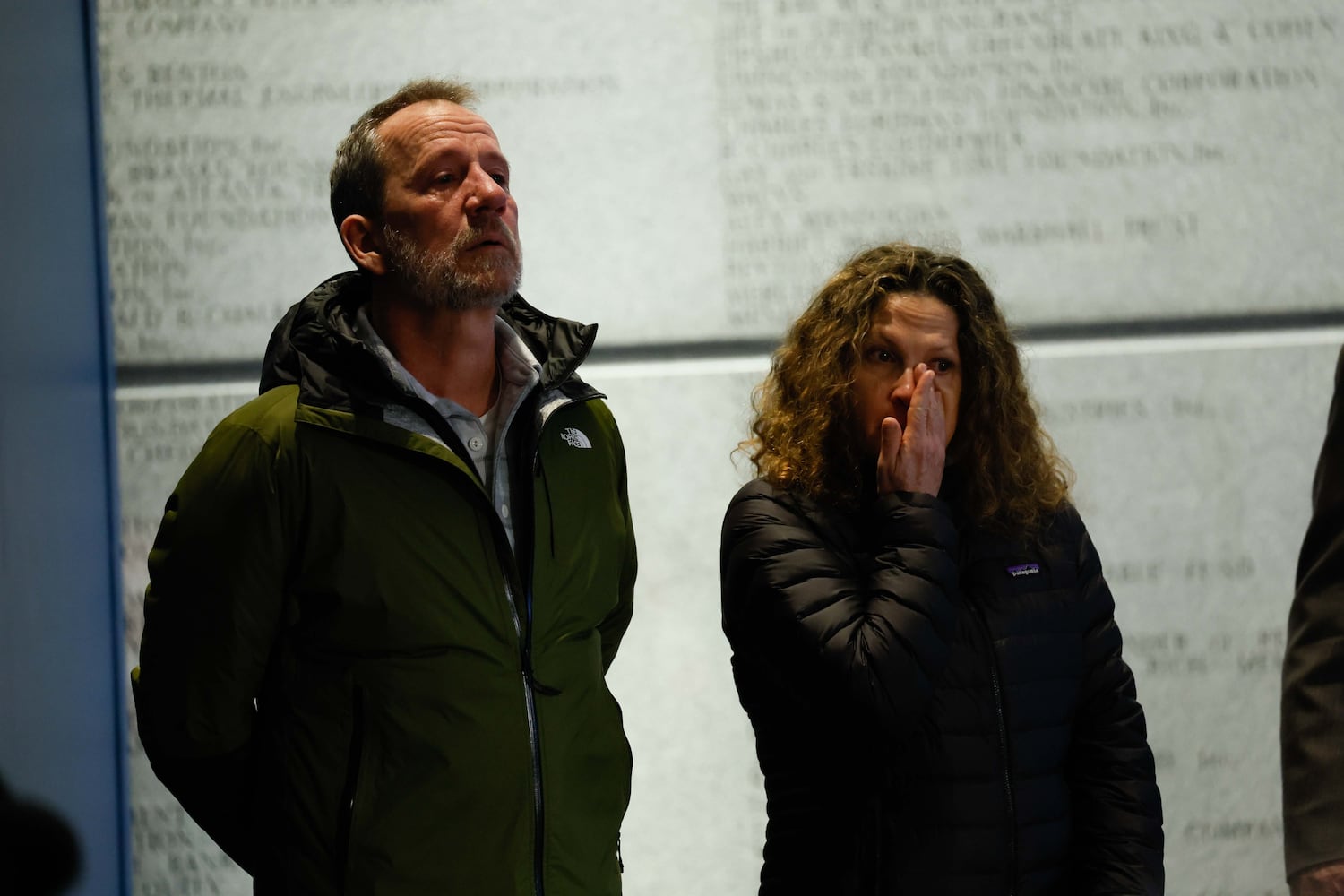

Carter lived his values centered on service and human dignity

Credit: Handout

Credit: Handout

For Carter, that moral imagination and focused action led him to state unpleasant truths and take on seemingly impossible challenges.

He declared that “the time for racial discrimination is over” in his inaugural address as governor of Georgia. He brokered, against all odds, the Camp David Accords, the most durable of any Middle East peace agreement, which is still in effect after almost five decades.

He put unprecedented focus on human rights in the U.S. and around the world and transformed the makeup of the judiciary with record numbers of women and minorities. His presidency was captured by his Vice President Walter Mondale in these simple but powerful words that seem almost quaint today: “We told the truth, we obeyed the law and we kept the peace.”

Following his reelection loss, a resilient Carter told The New York Times in 1989 that he did not want his presidential library to be a “monument to me” but an action-oriented center for the better world he imagined. He succeeded.

His Nobel Peace Prize citation notes his leadership of the Carter Center as “decades of untiring effort to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and human rights, and to promote economic and social development.”

Civic virtue is a part of the USA’s DNA

Credit: Jimmy Carter Library

Credit: Jimmy Carter Library

For his entire life, Jimmy Carter’s faith and moral imagination were the foundation for his civic virtue, the ancient idea that there is a way of being, necessary to sustain a republic, which balances the needs of the collective — the common good — with the individual’s needs.

For Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle, citizens with civic virtue were informed, active, selfless, enlightened and just. They prioritized the common good of the community or country over personal interests and took actions that strengthened the public sphere, all ideas important to our founders.

Founding Father and fourth President James Madison wrote that civic virtue in citizens was necessary to ensure civic virtue in our leaders. Carter as leader and Carter as citizen embodied it.

Civic virtue has not fared well in the last decade. A 2021 poll showed fewer Americans were committed to the common good. But there is hope. Pew Research found in 2024 that participants named not only better politicians but better citizens in the top five ways to strengthen democracy.

They had ideas on how to become better citizens that sound a lot like civic virtue. Some ideas were general — be more informed, participate more and, generally, be better.

Others were more specific: investment in the welfare of neighbors, practice care and patience, build community. And one was concrete: Get off social media for a month and talk to your neighbors.

Future leaders must learn from Carter’s follies too

Jimmy Carter was a truth-teller and prophet, a combination that did not serve him well. The media critic Eric Alterman pointed out in The Nation in 2004 that Carter “who earned a reputation for being painfully honest in public life, meanwhile, is considered a kind of political misfit within these same media circles, in which many seem more comfortable with a politician who ignores painful truths than one who confronts them.

Should Alter’s prediction of a Carter-like figure for the 21st century come true, that leader will need to learn from Carter’s communication challenges because public communication is the medium through which the national fabric is woven, as presidential rhetoric scholars Karlyn Kohrs Campbell and Kathleen Hall Jamieson have noted, and our national fabric is in danger of rending.

We will strengthen our democracy by rewarding, not punishing, that future moral leader for communicating and confronting unpleasant truths and acting on them for a better world.

But that will happen intentionally not accidentally, with preparation not happenstance. The best way we can honor President Carter on this one-year anniversary of his death is to commit ourselves to civic virtue, balancing our individual needs with the common good and electing leaders who commit to do the same.

We will let our moral imagination soar to envision a better world and to work to achieve it. We will see possibilities beyond our immediate self-interest and come together for the greater good. Our republic depends on us.

Linda Peek Schacht served in the Carter White House and 1976 campaign and was communications director for the 1980 presidential re-election campaign. She is a former Coca-Cola Company executive, Harvard Kennedy School Fellow, and founding director of Lipscomb University’s Andrews Institute for Civic Leadership. She teaches political communication and leadership at Emerson College. She resides in Atlanta.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured