My hero died Saturday. At our last visit, my wife and I sat for one of our regular lunches with Dr. Bill Foege and his wife, Paula, in their pretty Atlanta house.

Paula, a devoted partner who has followed Bill all over the world through many battles for more than 60 years, was still right next to him.

Though weakened and gaunt, the old warrior — white-haired and white-bearded, 6-foot-7 in his prime — was still himself, showing flashes of his globe-trotting brilliance and big heart.

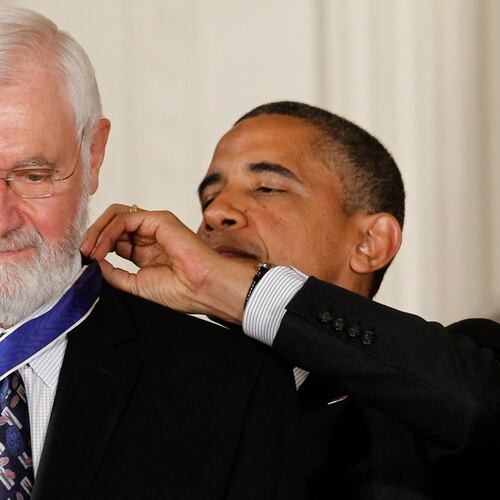

He played a key role in the eradication of smallpox as the architect of the strategy for effectively employing the smallpox vaccine. For his work on this he was nominated by President Jimmy Carter for the Nobel Peace Prize and awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama in 2012.

As director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, he led the effort to broaden its focus from only infectious diseases to applying the public health approach to chronic and environmental and work-related illnesses to injuries and violence.

He emphasized the value of prevention and a focus on social and economic determinants of illness. He showed the importance of coalitions by getting UNICEF, the World Health Organization, World Bank, U.N. Development Program and the Rockefeller Foundation to collaborate on immunizing children in resource-poor countries and created the Task Force for Child Survival and Development.

Bill developed new partnerships with the private sector to address widespread neglected tropical diseases through what he called pharmaco-philanthropy, mobilizing coalitions to eliminate a series of neglected tropical diseases that disabled and disfigured hundreds of millions of the world’s most neglected people.

He mentored several generations of leaders in global health and worked with Bill and Melinda Gates to bring the foundation world into partnerships with the countries that suffered from these diseases, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and polio.

Foege espoused 9 lessons and 3 essentials for making the world better

Credit: Hand

Credit: Hand

As my boss, my mentor and my friend, we worked together for more than 50 years on most of these initiatives. I was far from the only person to be so deeply touched by Bill.

His legacy will live on in the hearts of thousands of people around the world that he touched, mentored and supported. There are several generations of public health workers who feel that Bill changed their lives. Some of the people who wrote to say they feel deeply changed by Bill’s teachings had never even met him. Teaching and supporting young workers and students were very important to him.

In all the time I spent with him and all the teaching and travel we did together, I never saw him walk away from a student with a question. Even after stopping to talk to a student caused us to miss a flight back to Atlanta.

“Who takes the credit,” he said, “is not important, but credit is infinitely divisible and giving it away really matters.”

Credit: Charles Dharapak/AP

Credit: Charles Dharapak/AP

Bill showed me that even while working hard and doing good, you can have fun and have a sense of humor. In fact, the humor made the hard things easier. He was a world-class practical joker.

For years we had diet contests, racing to see who could lose the most weight. I tried to sabotage him with late-night deliveries of pizza and beer, and after losing every time, I showed up for one weigh-in determined to win wearing just a bathing suit. He came fully dressed, even with a sports coat. He suggested we weigh ourselves three times and choose the lowest weight.

After the first weigh in, I was ecstatic — I finally won! But on Bill’s next weigh-in, he removed two heavy books and a pile of coins from his pockets. On his last weigh-in, he pulled, from his socks, a heavy metal statue. He won again.

How did he do it? He focused relentlessly on becoming a better ancestor, always asking, “What do our decisions every day do for those born 300 years from now?”

He worked hard to put together ″9 Lessons to Change the World,“ an important part of his legacy for his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren — and for all of us with an interest in making the world a better place.

He came to believe that “there are really three essentials:”

- “No. 1: Try to get the science right.

- “No. 2: Try to get some creativity into that science.

- “And then No. 3: Include a moral compass.”

Most fundamental of all, he always said, is the golden rule: Treat others how we would like them to treat us. He boiled his formula down to three words: global health equity.

An apt description of him: ‘AI with a moral compass’

In the end, Bill lived with an extraordinary amount of pain and severe congestive heart failure. He made it a point to never burden others with his pain. Part of the pain was from a chronic hip problem that had plagued him for years and years.

“BTW,” he wrote to me after a physician visit, “my hip exam. Pain probably due to lysis of bone from slivers off the prosthesis for 31 years. Options include replacing hip, a major operation at this point and would not necessarily help since the joint is still intact. Option 2 is to have pain until I die. Option 3? He said there is no Option 3.”

He feared that what was happening to public health was not just the result of incompetence or ignorance, but he felt that there were forces and people of evil who would be hurting generations to come.

Over the holidays I sent him my favorite photo, a picture of four sisters in a remote Mayan village in Mexico. I love this picture because the four sisters did not smile for the camera because they had never even seen a camera before. To me they are open, honest, tender and connected. They are vulnerable and human.

Credit: Mark L. Rosenberg

Credit: Mark L. Rosenberg

Bill saw something very different: “Your pictures are powerful. Those four girls gazing into a bleak future should haunt us all.” I saw his comment about the four sisters as very revealing of what was going on inside him. What he feared was happening to public health was even worse than the pain.

He was our greatest living public health hero and it’s been the honor of my life to be his colleague, his lieutenant, his friend. How do you say goodbye after 50 years together? Most bitterly, he has closed his eyes without knowing for sure that America will get through this return to medieval faith in power and magic, as dark forces violently try to turn back the clock on civilizational progress.

I always used to turn to Bill to restore my sense of optimism. He sometimes called it unwarranted optimism. He was brilliant and had a memory unlike anyone I have ever met. He was AI with a moral compass.

Now, when I need it most, I am not going to have him anymore. But always thinking ahead, he left us a set of principles to safeguard our public’s health. He also gave us the example of a hero who had the courage and the heart to use them, not just to improve the public’s health, but to improve life in so many ways.

He transformed students — especially students in developing countries — and the institutions he helped to shape, and an army of thousands that he mentored and inspired. We also have millions of people around the world who are alive today because of this real hero.

Mark Rosenberg was Assistant U.S. Surgeon General and the founding director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. He is president emeritus of the Task Force for Global Health.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured